2023 | Volume 24 | Issue 2

Author: Dr Peter F Burke FRCS FRACS DHMSA Specialty Editor-Surgical History: ANZ JSurg

The Kenneth Fitzpatrick Memorial lecture was founded by the College in 1991 to perpetuate the memory of Professor Ken Russell (1911-1987), who held a personal chair in anatomy and medical history in the University of Melbourne.

Ken was not one to mince his words. He wrote of Claudius Galenus (anglicised to Galen born in 131 and died in 201): ‘Galen was a Greek physician who practised in Rome. He was the first experimental physiologist and became a medical dictator whose works were accepted with complete authority until the Renaissance.’

Dr Herbert M Moran FRACS, author of Viewless Winds and Beyond the hill lies China, wrote an autobiography, In My Fashion, in the months before to his death, from metastatic melanoma, in December 1945.

The final chapter starts thus:

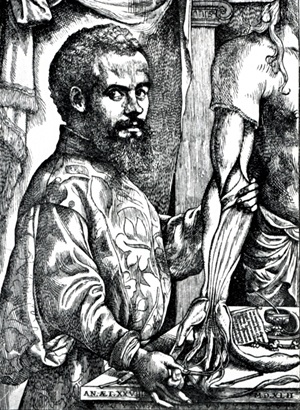

‘The phases of a doctor’s life are often three. The story of Vesalius shows it well. There was that first fierce stage of youthful curiosity and research when a restless mind challenged, with courage, the teachings of Galen, which had become almost a dogma of the Church.

Image: Portrait of Andreas Vesalius

This was the fertile season of his mind: but soon we find him in the second stage: after the enjoyment of so great an achievement, and after bitter criticism, he is at ease in a courtly life, all effort at research slackened. It is a base period of private satisfaction and public adulation. Now he has reached the philosopher’s phase; the last, when the worthlessness of things ephemeral appals him.’

This, then, is the story of the man who single-handedly dared to expunge Galenism.

Andreas Vesalius was born in 1515 in Brussels, as Andreas Wesele, latinised as Vesalius.

Descendant of a family of physicians and son of a pharmacist, he entered the University of Louvain where he studied philosophy, learned Latin, Greek and Hebrew; he also studied literature, but not medicine. After five years of study, he graduated at 19 years of age, a Doctor of Philosophy.

At Louvain, the facilities for medical education were poor. At the dawn of the 16th century there were four great centres of medical learning in Europe—Bologna, Padua, Montpellier, and Paris. Young Vesalius was dispatched to Paris.

The medical faculty at Paris had remained under the domination of scholiasts, and practical instruction was almost non-existent. Nevertheless, Vesalius started to dissect, but his studies were interrupted in 1536, by the war between France and the Holy Roman Empire: he had no option but to return home, with no further qualification.

Vesalius then travelled to Italy spending his first months in Venice where he befriended one of the artists in Titian’s school, a fellow Fleming, Jan Stephan Calcar.

Keen to obtain medical qualifications, he proceeded to attend the University of Padua, which was then at the height of its splendour, attracting students from all over Europe. His teachers quickly recognised his outstanding knowledge and ability, and within two years, permitted him to sit his final examinations: Vesalius gaining his doctorate just before his 23rd birthday.

Within a week of graduation, he became Professor of Anatomy and Surgery at Padua; he was not yet 24. Vesalius soon established a reputation for first-hand knowledge of the dissected human body, aided by working as public prosector at Padua for five years.

He had come to Italy, an intense Galenist, to verify by actual dissection the pronouncements and teaching incorporated in Galen’s texts. As he worked, he found Galen, the ‘infallible’, in repeated error. Gradually it dawned on him that Galen never dissected the human body but had transmuted to man, the anatomy he had found in apes and pigs.

Not only was Vesalius an assiduous anatomist, but he was also an experimenter and a surgeon of wide European repute. He showed that animals could survive splenectomy, that the brain acted on the trunk and limbs through the spinal cord, and that the lungs shrink on opening the live chest.

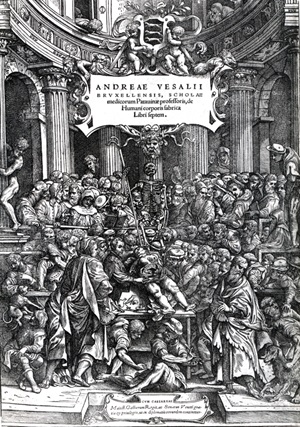

His anatomical research culminated in 1543 with the publication of his magnificent volume entitled De Humani Corporis Fabrica libri septem, which translates as, Seven books on the fabric of the human body. This work of more than 600 pages and comprising seven volumes and containing more than 270 illustrations was described by Sir William Osler as: ‘The Fabrica remains a monument of human effort, one of the greatest in the history of our profession.’ Three editions were published.

The 28-year-old Vesalius took extraordinary care to ensure that everything about his book, the paper, type, illustrations, layout and production were worthy of his text. Using his connections with Titian’s school at Venice, primarily with Jan Calcar, the true anatomic norm was first attained, a picture both scientifically exact and artistically beautiful. The splendid wood cuts representing majestic skeletons and flayed figures, dwarfing a background of landscape, set the fashion for over a century, and were copied or imitated by countless anatomic illustrators.

The woodcuts were fashioned in Italy and taken to Basel in Switzerland by Vesalius, on sabbatical leave, to the famed printer, Johannes Oporinus. The result—a superb example of beautiful typography: the cost of its production enormous.

Its pages presented for the first time the study of the structure of the human body as a system, which before had been nothing but chaos. It had needed a sustained ambition, and an incessant thirst for knowledge, and for truth, to produce the orderly text of the seven books within the period of just five years.

The magnificent frontispiece, the work of Calcar, contains many fascinating symbolic images—too many to detail here.

Image: Jan Calcar’s magnificent frontispiece for ‘De Humani Corporis Fabrica’.

In just one instance, amid the turbulent body of students we observe the cowled figure of a monk—symbol of the Church—silent and impassive in the bitter quarrel between the Old Knowledge and the New, another student reads a book.

So stupendous a revelation could not appear without its detractors. The anger of the professors of the old school knew no bounds. The Galenists joined to a man in denying absolutely and vehemently, the truth of Vesalius’ statements. Sylvius, his old teacher, turned against his brilliant pupil with acrimony and coarse abuse: others joined in a conspiracy of silence.

Thus, while Vesalius’ fame became greater and greater, on every side the most violent accusations arose. In a fit of indignation Vesalius burned his manuscripts, left Padua, and accepted the lucrative post of physician to the Imperial household of Emperor Charles V, and, in 1556, to Philip II, his son and successor. Vesalius married, settled down, became a courtier, and

abandoned anatomy completely.

Subsequently, Fallopius, a loyal pupil of Vesalius, who had succeeded to the Chair of Anatomy at Padua, died, in 1562. In 1563 Vesalius set out alone on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, some say as a pretext for getting away from his tiresome surroundings at the Court, to enable his return to the Chair at Padua.

In 1564, on the return journey through the Mediterranean, he was shipwrecked, on Zakynthos, a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, west of the Peloponnese. Stricken with severe illness, and died alone, far from his family.

He was scarcely 50 years old. His name upon no part in eponymous anatomical nomenclature.

Among the priceless treasures of our College’s Cowlishaw collection, lies a second edition Fabrica of 1555, and a third edition of 1568. By way of comparision, Cambridge University holds four copies of the first edition and two copies of the second edition.