2024 | Volume 25 | Issue 3

Author: Dr Peter F Burke, FRCS FRACS DHMSA

The Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS) will celebrate its centenary in 2027 with justifiably great pride. Appropriate planning is underway to mark this milestone.

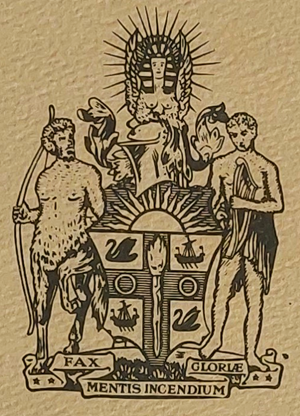

The golden jubilee of the College was celebrated in 1977, the year that your author was ‘duly admitted by the Council a Fellow’ of the College. In all the excitement of gaining the coveted diploma, it must be admitted that little attention was paid to the arms of the College, seen here in figure 1, as illustrated on said diploma.

Recent correspondence with the College of Arms in London yielded the following information: ‘The 1931 grant to the College of Surgeons of Australasia (which very shortly afterwards became the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons) is on record here with reference Coll. Arms MS Grants 98/139’.

The Grant of Arms, also called Letters Patent, is a manuscript document, written on parchment, issued by the Kings of Arms, the most senior heralds of the College of Arms.

Some years ago, the RACS Council decided to update the College branding, the principal reason being that the Coat of Arms did not work well in the digital space. An agency undertook all the design work and presented it to Council, who approved the new logo, which has several elements to it: a shield shape, an ‘S’ shape for ‘surgeons’, and a scalpel shape. (Figure 2)

Modernisation of organisations however continues a disappointing trend, distancing them from their origins, and especially, in the case of RACS the most important Grant of Arms in 1931. The two must and can co-exist harmoniously.

The attention of the reader is drawn to a ‘special article’ published in the ANZ Journal of Surgery 10 years ago, namely, ‘The arms revisited’1, written by the late Dr Wyn Beasley, Honorary RACS Aotearoa New Zealand archivist.

In the same issue of the journal, an editorial, ‘Fax mentis incendium gloriae’ 2, served to introduce Professor Beasley’s article, providing information to the subject matter of arms, armory, and armoury.

Figure 3 illustrates the Australasian College of Surgeons’ arms, with its specific ‘heraldic’ features, anatomically labelled, to provide clarification.

The simple flat bands of painted colour superimposed on the field of the shield are called ‘ordinaries’, in the case of the College—the Cross of St George.

A shield is said to be ‘charged’ with the devices upon it, which may be used singly or in numbers. For RACS, the ‘charges’ include two black swans emblematic of Australia and two lymphads from the Aotearoa New Zealand national arms. ‘Lymphad’ is derived from Scottish Gaelic, and refers to a long, single masted ship, propelled by oars.

Heraldry, or more accurately, armory, became established as a system during the second half of the 12th century.

The Earl Marshal was in former times, with the Lord High Constable, the first in military rank under the King who usually led his army in person. The Earl Marshal is now Head of the College of Arms, which comprises three Kings of Arms, six Heralds of Arms, and four Pursuivants of Arms.

These 13 College of Arms personnel are also officers of the royal household and are appointed by the Crown on the nomination of the Duke of Norfolk, Earl Marshal of England. Apart from their duties on state occasions the members of the College investigate claims to bear arms and arrange for the granting of armorial bearings: heraldry and genealogy have been closely linked since Tudor times.

To paint or draw a coat of arms is to ‘emblazon’ it. To describe a coat of arms in words is to ‘blazon’ it. All ‘Grants’ or ‘Confirmations of Arms’ are formally recorded with a full blazon of the insignia at the College of Arms.

The language of early blazons was French or Latin, later they became anglicised and gradually became extremely complicated. A full display of armorial bearings is called an ‘achievement of arms.’

A coat of arms is configured by means of the technical written description, the ‘blazon’, not by any particular artist's depiction. For example, one of RACS supporters is, ’a representation of Chiron,—the centaur, but how exactly Chiron is depicted is at an artist's discretion, thus one could commission new artwork of the RACS coat of arms, in a more contemporary artistic style than the original 1930s artwork. The key thing is that any new artwork faithfully reproduces the blazon.

For example, the official blazon of our College crest, as stated in the Letters Patent is, ‘In front of the suns rays or a Sphinx affrontee proper winged Gold’: translated to: Heraldic/contemporary: Or/gold, yellow: affrontee/full-faced: proper/natural colours.

In other words, there is much left to the artist's discretion. The sphinx does not need to be bare-breasted; the blazon does not even specify that it is an Egyptian sphinx rather than Grecian.

To circumvent the problems associated with the graphic reproduction of the College arms, on letterhead and the like, the contemporary approach is the use of logos, which in heraldic terms, are ‘badges’. These are supplementary devices sometimes repeating an element from the arms or crest, which can be displayed alone, or in association with the arms: they are not an integral part of the arms or crest.

The question now arises as to which ‘charges’ or elements present in our College arms could be incorporated into a badge or logo, given that a scalpel is not among these devices.

Commonly used is the Fax Mentis or ‘torch of the mind’, which is highly appropriate. A dominant feature of our arms is the Cross of St George, dating from the Crusades of the 10th century.

Also to be considered are the serpents, depicted in the College arms as in a circle, each serpent with its tail in its mouth, the ancient symbol of eternity. The serpent’s constant appearance in British armory, reflects its symbolic acceptance as the sign of medicine. Many grants of arms made to doctors and physicians introduce in some way, either, the serpent, or the rod of Aesculapius, or a serpent entwined round a staff.

The College of Arms in London was founded in March 1484. Current correspondence confirms willingness to assist, if requested, in the design of a College ‘badge’, perhaps more representative of our very proud and almost century-old, coat of arms.

References:

1. ‘The arms revisited’ Wyn Beasley ANZ J Surg 84 (2014) 12-16

2. ‘Fax mentis incendium gloriae’ Peter F Burke ANZ J Surg 84 (2014) 1-3

Figures:

1. Detail of RACS arms from 1977 Fellowship diploma.

2. The contemporary College logo.

3. The annotated arms of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons.