2024 | Volume 25 | Issue 5

Author: Associate Professor Felix Behan, AM

This is a strange title for a Surgical News article but there is an historical overtone with a surgical flavour and I am reverting to Ernest Hemingway’s quote: ‘Any story based on truth and a good story, is worth telling’.

This all came about following a recent SBS documentary Rise of the Nazis and the liberation of Paris on 25 August 1944 and its 80-year anniversary. The program focussed on the US control in west Berlin after the war and the manhunt for fleeing Nazi war criminals like Eichmann and the Butcher of Lyon—all of whom were responsible for gross atrocities. Their escape routes were titled the ratlines, which was how they avoided the hangman’s noose.

The security wing of the US forces from the State Department was called the Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) and the person in charge was Robert Taylor. How coincidental. This name sparked my mind into a recollection phase recalling my past experiences at the Royal Brisbane Hospital (RBH).

How could one forget the name Robert Taylor—the Hollywood actor who featured in such films as Magnificent Obsession and Yankee in Oxford and was so handsome that he was the apple of every girl’s eye.

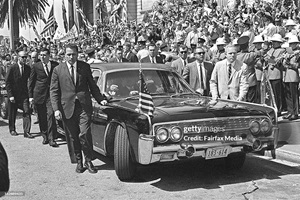

However, historically when President Lyndon Johnson visited Australia in 1966, he had his usual big security entourage to accompany him.

Presidential entourage

It so happened I was working in the emergency department at the RBH on that afternoon in charge of admissions when the US entourage arrived, seeking urgent medical attention. Why? One of the limousines—Buick or Cadillac drove over the foot of one of the security guards at the rear, fracturing his toes. He was registered, x-rays were performed, treatment organised and how could I forget his name—Robert Taylor, but not the actor!

The fractures were treated, the foot splinted, no doubt done by Jock Bing, the plaster orderly, who worked in casualty at the time and trained in the Orthopaedic units in Scotland and taught us all how to apply a Colles plaster. And in my days at Preston and Northcote Community Hospital (PANCH) when one of Sir Benjamin Rank’s trauma cases also needed a Colles plaster, which I offered to do, Benny said to me: “Son, I am quite capable of doing this as I have been trained in Orthopaedics as well”. Then we treated the patient’s facial injuries from a motor car accident.

Back to the RBH. When the presidential medico arrived to supervise our management protocol, he was carrying a silver-grey metal suitcase, which never left his possession, handcuffed to his wrist. When I asked him what was in the suitcase, with my usual inquisitiveness, he replied that his refrigerated container carried the contents of cross matched blood for the president’s use, should the need arise.

The SBS program continued, and Robert Taylor featured prominently in the stories of the CIC and Nazi atrocities emerged throughout the documentary. Names like the Butcher of Lyon—Klaus Barbie—surfaced, who once went into an orphanage and shot all the children while orchestrating the transporting adults to the Dachau prison camp. He had said: “Children cannot be made prisoners of war”. Hence, all the children were shot, reflecting again Barbie’s narcissistic tendencies.

Oradour-sur-Glane village

Another item that emerged about Nazi atrocities was about the martyred village of Oradour-sur-Glane when the entire village and its inhabitants were shot, including children, as a reprisal against Resistance activities against the Nazis.

Jean Moulin building

President de Gaulle later stipulated that this village would remain an untouched permanent memorial site for the atrocities committed to the French in World War II.

My late French wife Mariette from Bordeaux would often recount these stories to the family over dinner throughout our married life. The French find it difficult to forget such atrocities of war they all experienced and admire their war heroes in the Resistance movement. On one occasion, back in Bordeaux, Mariette took me to the Resistance memorial building for Jean Moulin, one of their heroes.

My late French wife Mariette from Bordeaux would often recount these stories to the family over dinner throughout our married life. The French find it difficult to forget such atrocities of war they all experienced and admire their war heroes in the Resistance movement. So, who would have thought a television documentary 80 years after the liberation of Paris in World War II would feature the name Robert Taylor that jogged my memory from its somnolent phase, recalling my earlier medical experiences in Brisbane and the treatment of the presidential team—the name was crucial.

These vignettes would have been lost in history, but the SBS program brought it all back to the surface in the embryonic phase of my surgical developments at the RBH before I transferred to Melbourne in 1970—the leading centre in Australia at that time, to complete my training in Plastic Surgery. Then going on to train in London at the Royal Marsden and St George’s Hospitals.