2024 | Volume 25 | Issue 5

Author: Dr Glendon Farrow OAM FRACS

These were the words written by a doctor during my parachute medical in 1987. Years later that same doctor was shot five times by a disgruntled patient and survived, proving beyond doubt it is safer to jump out of perfectly good aircraft than be a general practitioner in Frankston.

I joined the 3rd Battalion Royal Australian Regiment (Parachute) (3RAR) for two years in 1987. I always wanted to be airborne. How hard could it be? Turns out, very hard indeed.

Military parachuting is challenging. Before exiting the aircraft, you have to deal with deafening aircraft noise, standing up with 30 kg of equipment while experiencing terrain-hugging flying and motion sickness. Outside there’s the blast of hot exhaust fumes, buffeting in the slipstream with possible collisions, then lowering your equipment on a line and landing. There’s no time for selfies.

The first week of training involved a lot of hanging around. We hung from a roof in parachute harnesses learning drills to control the canopy until our actions became automatic. We also dropped from 10 metre towers to practice landings. One paratrooper was nicknamed ‘The Refrigerator’ because that’s how he landed, in a cloud of dust.

Our first jumps were from the rear ramps of Vietnam-era Caribou aircraft. I had the ‘honour’ of being first. Stand up, hook on, check equipment, red light on, shuffle forward, look straight ahead, green light on, one step over the ramp hinge and you were gone. The next eight jumps were from C-130 Hercules aircraft using the rear side doors.

You have to push out into the slipstream to avoid scraping down the side, known as ‘counting rivets.’ Simultaneous side door exits carrying equipment are the most difficult and dangerous. Canopies overlap in the slipstream risking collision and entanglement. In my only collision I magically avoided entanglement and landed safely, shaking like a leaf. Those drills really worked.

The motto of the Parachute Training School is ‘Knowledge dispels fear’.

No, it doesn’t.

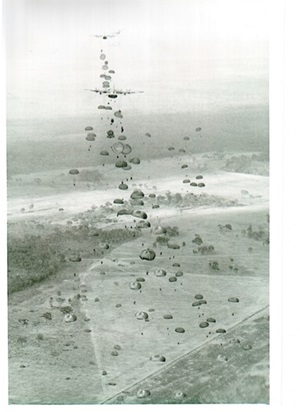

Fitting a parachute

In October 1987 3RAR jumped into Silver Plains in far north Queensland. After flying north over the Coral Sea, the aircraft turned inland and dropped to 300 feet hugging the terrain. We bounced around inside until the aircraft suddenly popped up to 800 feet, the G Forces pushing us into the floor. Just after dawn 450 paratroopers tumbled out of eight Hercules aircraft within minutes.

On landing I heard the shout, “Doc, there’s been an accident.” Stumbling across the drop zone I entered the resus tent to find everyone staring at the soldier’s compound leg fractures, but no one looking after the airway. His parachute failed, and he had ‘speared in.’ I went back to the primary survey, but he died from internal injuries. Like the song, he was only 19(1).

His death felt personal. I had just jumped in, like he had. Fate had dealt him the cruellest of hands. There’s a special bond between doctors and their battalions, probably through shared hardship, and I had let him down.

Three months later lining up for the first jump after the accident, I noticed a stretcher carrying a body bag in front of us. The bag slowly unzipped from the inside and out jumped the officer in charge rubbing his hands with glee.

“Right! Who’s ready to jump?”

Well, not me. But if you insist.

I jumped the minimum required after the accident and later wrote a paper on parachute injuries as a prerequisite for surgical training(2) , hoping to learn something from my two years there.

3RAR Battalion drop: Silver plains, 1998

I still have my faded airborne beret. Sometimes I put it on and remember when ‘I was a soldier once, and young’ (3) .

The beret

References:

[1] I was only 19, John Schumann, Redgum, CBS Records March 1983

[2] Military Static Line Parachute Injuries, G.B. Farrow, Aust NZ J Surgery. 1992, 62. 209-214

[3] We were soldiers once, and young, Lt Gen Harold G Moore 1997 Random House ISBN: 0-679-41158-5