2024 | Volume 25 | Issue 6

Leslie Cowlishaw

“… to instill a little culture into the average Australian practitioner, who at present, owing to the absence of proper library facilities, is in danger of merely becoming a skilled artisan and lacking any knowledge of the great profession to which he belongs,” Leslie Cowlishaw.

Leslie Cowlishaw, physician, bibliophile and advocate for the discipline of medical history, would approve of how easily we can now research medical history.

This was not always the case. In the 1920s Cowlishaw was one of the prime movers in the establishment of the Medical History and Literature sections of the New South Wales Branch of the British Medical Association. He believed all Australian medical schools should have a medical history department and vigorously campaigned for access to research material.

By 1938 Cowlishaw’s advocacy had borne some fruit and in the same year, he was made honorary lecturer in medical history at the University of Sydney. A series of 12 lectures—illustrated by glass lantern slides and books from his library—was delivered to final year medical students.

Cowlishaw’s glass lantern slide collection is now one of the hidden gems of the RACS archive. Despite their age, the 1450 slides are in excellent condition, and offer glimpses into Cowlishaw’s eclectic interests. His collection showcases a wide variety of subjects—from great figures in medical history to the medical practices of ancient civilizations, including Sumeria, Assyria, and Crete. Indigenous cultures, especially those of Australia and America, are also represented, including glimpses into Arab, Jewish, and Icelandic medicine.

Among Cowlishaw’s slides are portraits of philosophers like René Descartes, whose work connected philosophy and physiology. His slides also boast of paintings by 17th-century Dutch artist Jan Steen, whose genre scenes of medical life have moralising undertones.

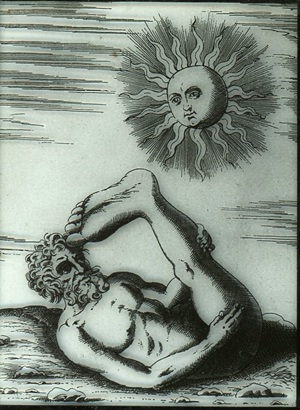

Cowlishaw slides - Sciapodes

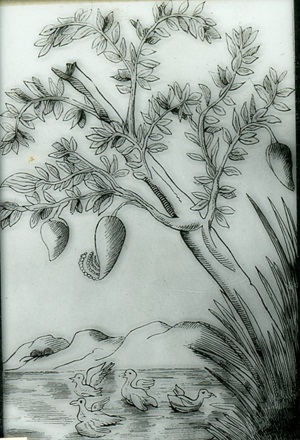

Cowlishaw’s slides include a whimsical and strange collection of mythical creatures, such as the Sciapodes—agile men who shaded themselves with their large foot—and the Barometz or Tatary Lamb, a plant-attached creature with honey-like blood. There are images of barnacle geese, believed to hatch from barnacle pods—a legend of the medieval period. These images served as a reminder of how medicine’s evolution has been interwoven with imagination, myth, and the ever-changing perceptions of reality.

Barometz/ Tartary Lamb and Barnacle geese

Cowlishaw’s fascination with these legends likely stemmed from the way they paralleled the early development of medical science, a field often seen as equally fantastic in its promises and discoveries. His slides are an enduring testament to a world where science and myth intersected, enriching our understanding of medicine’s roots in cultural and intellectual history.

How would Cowlishaw have interpreted these singular perceptions of reality? Their origins were in the classical world and were perpetuated by the herbals, literature and art of the medieval and Renaissance periods. It is no coincidence that many of Cowlishaw’s slides belong to this period because paralleling such ‘fantasy’ was the emergence of perhaps an equally fantastic science—the discipline of medicine.